Researchers Enlist Community Help in Studying Increase of Ticks in Western Maryland

Frostburg State University is working with the Department of Natural Resources to study the spread of ticks and provide more community information

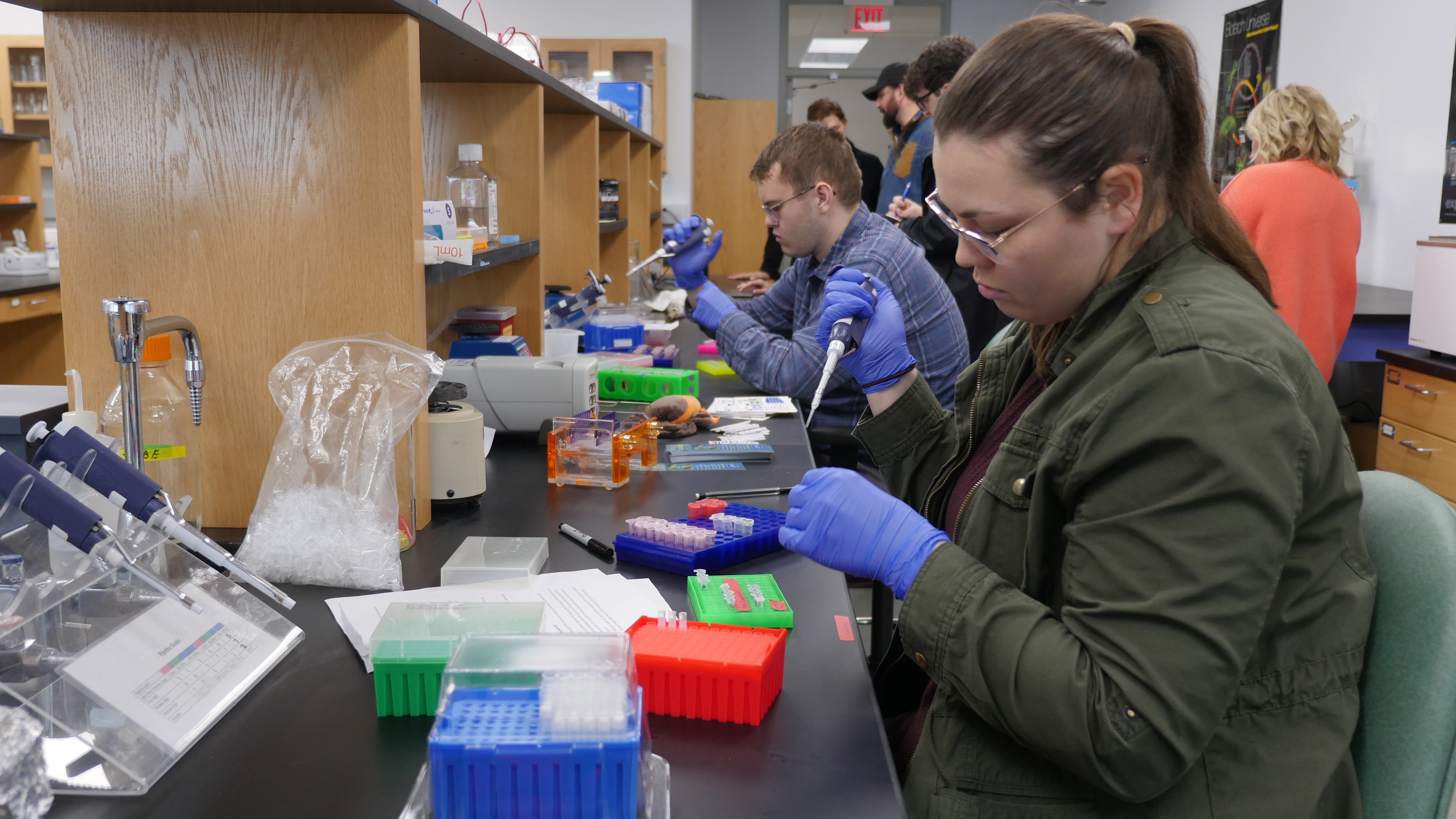

Frostburg State Students Sarah and Alex test ticks for Lyme disease as part of the “Tick Talk” program being led by Frostburg in partnership with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Photo by AJ Metcalf, Maryland DNR.

Ticks were once rare in Western Maryland, but the disease-carrying arachnids are on the rise in the region.

The Maryland Department of Natural Resources and Frostburg State University are working together on an initiative to study the rising prevalence of ticks and Lyme disease in western Maryland.

Rebekah Taylor, associate professor and chairwoman for the biology department at Frostburg State University, said ticks were not a concern in Western Maryland when she was growing up there. But things have changed. She started studying ticks after her son contracted Lyme disease.

“I wanted to look into what’s happening in my hometown,” Taylor said while presenting the project at a Tick Talk event Oct. 18 as part of DNR Science Week. “We should talk to people about ticks now because they’re here.”

As part of a citizen science effort, Taylor and Sarah Milbourne, acting western region manager for Maryland Park Service, are asking residents of the region to mail in ticks that they find by taping them onto specially designed postcards. The residents write the date and approximate location where the tick was found on the postcard, and Taylor and her research students identify the ticks and test them for Lyme disease.

They are making their data public on FieldScope, a data visualization website for community science projects, to inform residents about the risks in their community.

Ticks are becoming more common as a result of warmer winters, less intense forest management, and the spread of invasive plant species such as Japanese barberry–a favorite home of mice, which carry ticks. Research has linked climate change to both expanded ranges and increased seasons of activity for ticks.

Milbourne believes talking about talks is an effective way to communicate the everyday effects of climate change in a region not directly affected by sea-level rise or other prominent climate impacts.

“People care about ticks,” Milbourne said. “It’s something you can point to that has changed.”

Lyme disease, caused by a bacteria carried in blacklegged ticks (also known as deer ticks), leads to headache, fever and fatigue and can affect the heart and nervous system if left untreated. Taylor, who has a background in immunology, said doctors are advised to treat with the assumption of Lyme disease when more than 30 percent of nearby ticks are carrying the bacteria.

In their testing so far, Taylor’s team has found about 40 percent of ticks from the region were positive for Lyme disease.

Taylor said the postcards provide a way for people to play an active part in the research that affects their community. Milbourne plans to place the postcards at state parks, such as Rocky Gap State Park, so visitors can help the project if they encounter a tick on the trails.

In addition to the mailed-in ticks, Frostburg researchers have conducted field surveys by dragging flannel cloths through forested areas to collect ticks. When they remain in wait on the forest floor, ticks are often “questing”–holding two forelegs in the air, ready to grab a passing host–which makes them stick to the cloth.

The deer tick, or black-legged tick, is the most common tick in Maryland and the only one to transmit Lyme. However, other ticks can be vectors for other illnesses. The lone star tick, which has a distinctive white dot on its back, can infect people with ehrlichiosis, tularemia, and Alpha-gal syndrome, which causes an allergy to red meat.

Dog ticks often feed on canines, while the invasive Asian longhorned tick targets cattle and hooved hosts. The latter isn’t dangerous to humans, but it can reproduce without mating, allowing it to expand rapidly and making it difficult to control.

While Lyme disease is associated with a bullseye rash, as much as 30 percent of people infected will not have that telltale symptom, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Taylor also cautioned that many tick bites occur during the tick’s nymph stage, when it is smaller and more difficult to see.

Aside from demonstrating a tangible effect of climate change, Milbourne said she also hopes that the initiative provides people with guidance about ticks in their area and how they should be prepared for them.

Taylor said it was important to her that the information they collected was accessible and useful to the public.

“Everybody can have access to see what kind of ticks are in my backyard, what should I be worried about,” she said. “It has a lot of power to it. People can just look this up and find out what’s happening.”

By Joe Zimmermann, science writer with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources.