New Land Purchase Gives Wills Mountain State Park a Path for Public Access

Environmental cleanup and ecological survey will take time, but officials look forward to opening the long-inaccessible park

Just past the stone ruins of an old hotel, Maryland Park Service Ranger Cliff Puffenberger came to a clearing.

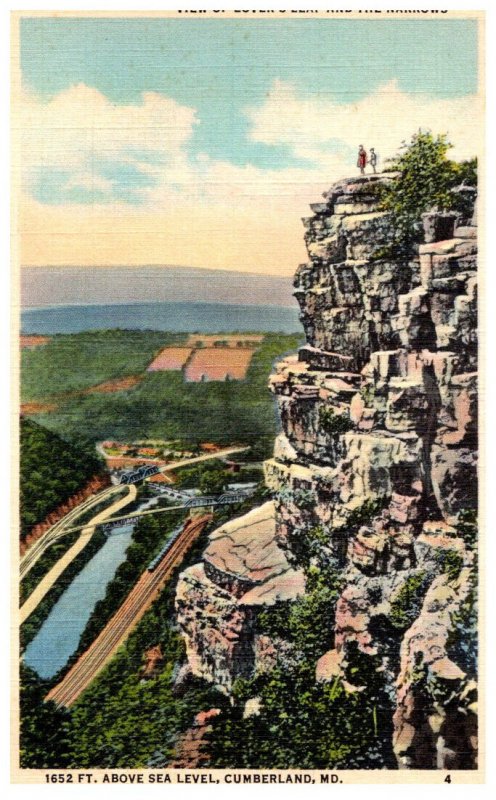

The edge of an outcrop revealed green mountains that filled the horizon and birds of prey that swept over rocky cliff faces. The expansive view, which stretched from Pennsylvania to West Virginia, overlooked the nearby city of Cumberland and the roads and rail lines that made it a hub of transportation in western Maryland.

“This is a magical place, it really is,” Puffenberger, manager of the nearby Rocky Gap State Park, said.

The lookout is part of Wills Mountain State Park, a scenic stretch of land in Allegany County that’s been officially inaccessible to the public for decades. But a new property acquisition by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources will open the way for public access.

In March, the department purchased the former Artmor Plastics Corporation property, which spans 48.53 acres, for $250,000. The area, which is adjacent to the previously acquired park property, includes a private road up the mountain that will enable the state to open Wills Mountain State Park to the public.

Though this is a critical first step, department officials said the park will still take some time to officially open as staff improves access to the site and gathers ecological and historical information about the park land.

Many look forward to the long-awaited opening, which represents a chance to preserve an ecologically rich area while offering recreational and economic opportunities to the community.

“Wills Mountain creates greater opportunities for diversifying our outdoor recreation in Allegany County,” said Ashli Workman, director of tourism for Allegany County. “This is really important for our destination, as this supports economic and community development. It means more people coming here, spending money, investing in, and exploring western Maryland.”

A historic linen postcard illustrates the view of the Lover’s Leap area of Wills Mountain, which overlooks a valley known as “the Narrows.”

Wills Mountain officially became a state park in 1998, when the Maryland Department of Natural Resources purchased the bulk of the current park property—about 305 of the current 520 acres. However, with the land located almost entirely on the ridge of the mountain and surrounded by private property on all sides, there was no way at that time to open the park to the public. In the years since, the department has added additional properties to the park and sought out areas that could allow for access.

Named after the possibly mythic 18th century stories of a Native American man named Will, the site has been at various points a center of activity that has since fallen into disuse.

It was once the site of a stately hotel, the Wills Mountain Inn, which boasted a grand ballroom and 46 bedrooms. Visitors drove their Model As up the steep mountain road backwards to prevent the gravity-fed engines from stalling out. The inn later became a sanitorium, which burned down in 1930.

The other prominent plot on the mountain was a textile factory during World War II and briefly a mountaintop nightclub—the Taberna Monteum—before Cumberland businessman Art Morgan bought the land and opened his Artmor Plastics factory in 1966.

Vacant since 2013, the Artmor Plastics building is now an imposing, abandoned structure, covered in vines and graffiti. Black vultures and turkey vultures perch together on the exposed roof, part of which collapsed after a 2015 fire.

“The cleanup of Artmor is going to be a significant process,” Sarah Milbourne, western region manager of the Maryland Park Service, said. “We need to make sure the buildings are removed in an environmentally safe way and then address lingering contamination.”

Vultures roost on the roof of the Artmor Plastics factory building, which once produced bowls, textiles, and other materials. Maryland Department of the Environment staff found presence of hazardous chemicals at the site after a 2015 fire. Photo by Joe Zimmermann

During the property acquisition process, an environmental assessment revealed evidence of hazardous materials left from previous industrial use of the site, said LeeAnne Chandler, chief of planning for Maryland Park Service.

The Maryland Department of the Environment has accepted the Artmor land into its Voluntary Cleanup Program, a program established to encourage the cleanup and redevelopment of properties with known hazardous substance contamination, Chandler said.

The next step will be for the Department of Natural Resources to prepare and submit a “response action plan” to the Department of the Environment, she said. Once that plan is approved, DNR can move forward with road construction, building demolition, and site remediation.

“Our hope is to eventually build a parking lot for park visitors in the vicinity of the old factory,” Chandler said.

Safety concerns related to the Artmor facility are part of the reasons why the Park Service has been increasing signage around the area letting people know that Wills Mountain State Park is closed and not to use the area, Puffenberger said. Wills Mountain currently falls under the management of Rocky Gap State Park. Maryland Natural Resources Police officers are also enforcing the closure by issuing warnings and citations.

Many visitors and residents have accessed the park over the years even though it’s closed, likely parking offsite and walking past the locked gate, he said. People hike the trails, and it’s a prominent place for outdoor rock climbing as well as bird watching.

The other reason the Department of Natural Resources is ramping up trespassing enforcement is that department staff have started an ecological review of the park in anticipation of its opening, officials said.

“Wills Mountain is a unique habitat in Maryland and it’s home to a number of rare and endangered species,” said Katharine McCarthy, a DNR ecologist and habitat conservation manager. “We have this important opportunity to document these species now before the park opens, so we know how we can protect them and access the space responsibly. Our surveys this spring have already revealed a rare plant, racemed milkwort, that was not previously known from the park.”

An ecological review is standard before the opening of a state park, she said, and requires that people not use the area so biologists can study how undisturbed animals and plants are living within the park’s boundaries. Because of the uniqueness of the site, the review will likely take at least one year to complete, after which the department’s biologists will issue a report and recommendations to the Park Service.

The Tuscarora sandstone and poor, dry soils support a barrens habitat at Wills Mountain, McCarthy said. The park supports a wide range of mammals, including black bears, fishers, Allegheny woodrats, Appalachian cottontail, and bobcats. A number of rare plants are also found in the park, from wild bleeding heart to umbrella sedge.

A trail camera catches a coyote and bobcat sharing a moment at Wills Mountain. Porcupines, bears, fishers, and other animals have made use of the area. Maryland DNR photo

Bald eagles investigate carrion at the park, which hosts many raptors as well as migrating birds. Maryland DNR photo

Megan Zagorski, the department’s western region ecologist, said acoustic recordings at the park have documented northern long-eared bat, eastern small-footed bat, tricolored bat, and either little brown bat or Indiana bat, which are difficult to distinguish by sound. Two of these bat species are federally endangered and others are state endangered or rare.

The cliff faces and rocky talus areas are beneficial habitats that may allow bats to survive the devastating white-nose syndrome, by giving them more space to spread out than they have when hibernating in caves and providing microclimates that may be less suitable to fungal growth, Zagorski said.

The cliffs are also one of only two known natural rock nesting sites in Maryland for peregrine falcons. Though the falcons will raise young on buildings and artificial edifices, this natural nesting is an important development for the species that bounced back from a steep decline caused by past use of the pesticide DDT, which was banned in 1972, Zagorski said.

The outdoor climbing in the area is of particular concern to biologists. The state has a mandate to protect these birds, which are a species of concern in Maryland, and Milbourne said department staff want to determine how rock climbing can continue without disturbing the peregrine falcons or other legally protected species before opening the area to climbing.

Striking that balance between human recreation activities and sustainable animal habitat is going to be a priority throughout the park, Milbourne said. The remoteness of the park is part of what has allowed species to thrive there, and she said the Department of Natural Resources wants to be careful in continuing to provide these species places to thrive when the park opens to the public.

Chandler, who worked on the 2022 opening of Bohemia River State Park, said site remediation and ecological review are standard procedures for opening a new park.

Though members of the climbing community and others have expressed frustration with the park closure, Chandler said taking time before parks open is a necessary part of the process. She pointed to Wolf Den Run State Park, the only Maryland state park to allow off-road vehicles, as an example of a park that took time to open but ultimately benefited both the recreational community and the ecology of the area.

“In the long run, it’s a much better experience, and we were able to build sustainable trail systems and ensure that inviting people out to the site is not going to create significant environmental harm,” she said.

A historic photo shows the Wills Mountain Inn atop the cliff. The stone foundation of the building still stands.

Part of building a new park will also involve bringing in the history of the area and the community. Kara Rogers Thomas, a sociology professor at Frostburg State University, teaches a class on Experiencing Appalachia, where students have conducted research projects on different parts of Wills Mountain. They then hand off their work to the Park Service.

“The students are really excited to be part of the work in being involved at this early stage of a new state park,” she said. “It’s also great to honor the rich history of Cumberland and Wills Mountain and keep that history at the forefront of the park.”

By Joe Zimmermann, science writer with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources.