Maryland’s Most Wanted: Join the Hunt for the Spotted Lanternfly

Since August of 2020, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources has conducted 64 different hunting seasons covering a variety of animals, seasons, and locations. But there’s one animal in particular that the DNR is very interested in, which has no hunting restrictions. For this species, you won’t need a spring trap or a rifle. A net to catch it with and a camera works much better.

Since August of 2020, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources has conducted 64 different hunting seasons covering a variety of animals, seasons, and locations. But there’s one animal in particular that the DNR is very interested in, which has no hunting restrictions. For this species, you won’t need a spring trap or a rifle. A net to catch it with and a camera works much better.

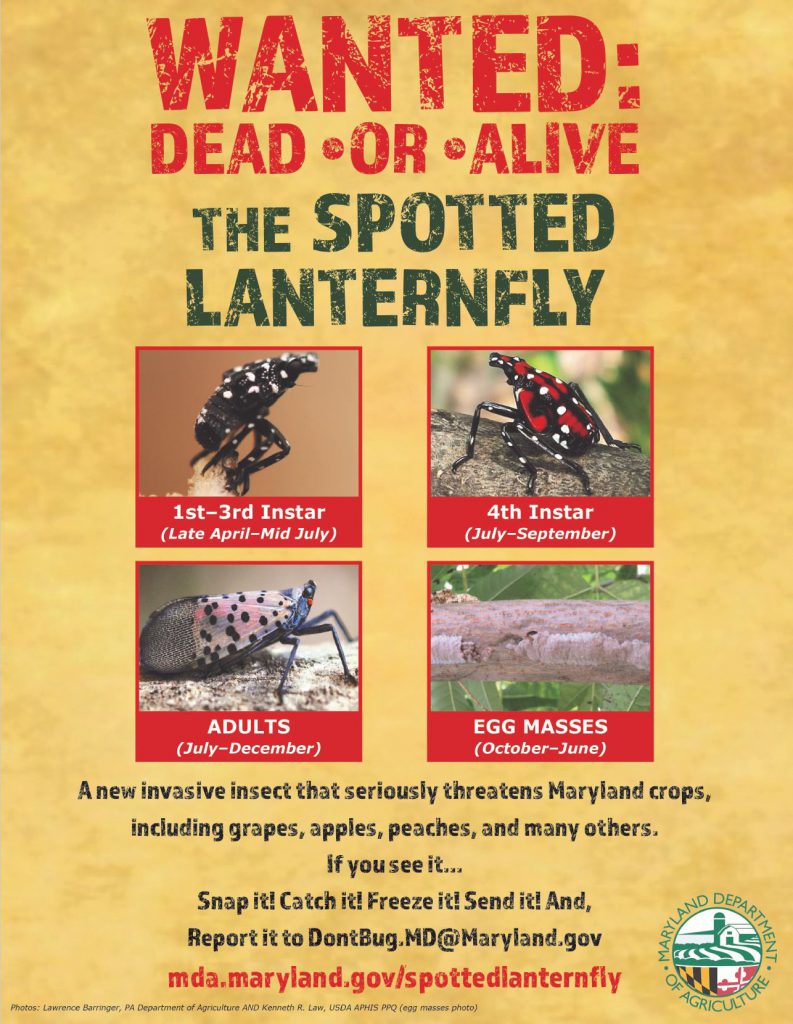

The species in question? The spotted lanternfly. It looks harmless enough, and it is to humans. But to many species of plants that we rely on for food, lumber, and shade, this invasive species is deadly.

In spring, spotted lanternflies hatch from eggs often laid on the invasive tree-of-heaven, but they can be found on anything flat and vertical. The newly hatched nymphs are black with white spots, and starting in July the oldest nymphs will also have patches of red. Shortly after, they will begin to assume their adult forms, which have wide colorful wings.

Spotted lanternflies mostly eat phloem—the vascular tissue in plants that conducts sugars and other metabolic products down-ward from the leaves, basically transporting the energy created through photosynthesis. Especially in the fall, spotted lanternflies will gather together and eat the phloem of an unsuspecting plant, eating the plant’s food and excreting honeydew. This by-product can create the perfect condition for mold to grow on leaves, stopping plants from photosynthesizing, and can cover and discolor manmade surfaces.

Spotted lanternflies can cause branches to fall off or can outright kill plants if the damage is great enough. And spotted lanternflies like to eat a lot of different plants. They can literally eat your lunch by feeding on almonds, apples, apricots, basil, blueberries, cherries, cucumbers, grapes, horseradish, nectarines, peaches, plums, and walnuts. They can eat the wood that makes up your table by noshing on hickory, maple, oak, and pine; and they could even mess with happy hour by snacking on hops. What’s more, there’s no easy way to deal with large numbers of spotted lanternfly. They can be killed by insecticides, but survivors are able to quickly return to sprayed areas. And physical traps that kill them also tend to catch other species that could be beneficial. Since the eradication of spotted lanternflies is such a complicated undertaking, the best defense against the spotted lanternfly is prevention.

And that brings us to some positive news and what you can do to help. Spotted lanternflies are not widespread in Maryland—they were first seen in the state in 2018, and Harford and Cecil counties in northeastern Maryland are under a quarantine order covering items that might inadvertently transport the pest. If you’re traveling out of Harford County or Cecil County, check your clothing and vehicle to see that you’re not harboring a hungry bug. We can’t stop them from traveling on their own, but we can stop them from using us for a free ride, and their weak flying ability makes this more effective than you might think for a winged insect.

Across the state of Maryland, if you see something that looks like a spotted lanternfly, take a picture and send it to DontBug.MD@maryland.gov or call 410- 841-5920. If you can, try to catch the bug, place it in a bag, and freeze it. Eradicating invasive species is a costly and challenging task, but stopping them from spreading and keeping tabs on where they are makes that job a lot easier.

dnr.maryland.gov/forests

Adam Larson is a Seasonal Park Ranger at Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad State Park. Article appears in Vol. 24, No. 3 of the Maryland Natural Resource magazine, summer 2021.

1-888-373-7888

1-888-373-7888 233733

233733