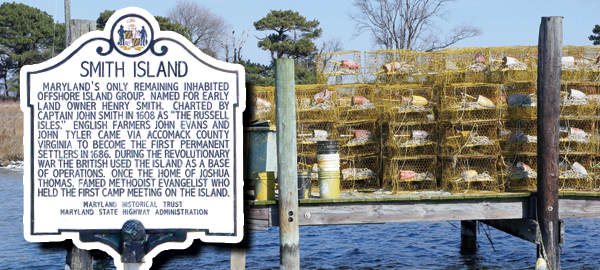

Saving Smith Island: A Vision Plan to Save the Future

Crab pots; by Stephen Badger

“Welcome to Mayberry,” jokes Eddie Somers as our boat docks at Smith Island’s Ewell—his hometown. With a total population of 276 year-round residents, it’s safe to say everybody knows everybody, even when part-timers arrive, swelling the population to upwards of 600.

Deliveries; by Stephen Badger

A Department of Natural Resources hydrographic engineer, Somers serves as my tour guide on this one-day visit. Though he and his wife now live in Crisfield, they plan to retire to their beloved island.

If you have lived in Maryland for any length of time, you have probably heard of Smith Island: a community first charted by Captain John Smith more than 400 years ago.

It’s accessible by a 45-minute boat ride. There’s an elementary school in Ewell, but high school students take the “school boat” to Crisfield to attend classes. A nurse and dentist visit regularly to provide healthcare, but more complex or urgent care requires a trip to the mainland. And what Marylander does not know about the famous Smith Island cake?

Despite knowing a bit about the island, this is my first visit.

My goal? To talk to residents about the Smith Island Vision Plan, a document of recommendations and strategies the entire community worked on, published in August 2015.

| Over the course of the Visioning process, discussions within the community quickly revealed several common themes that are integral to the future success of Smith Island: Sustainable Growth of Watermen’s Culture • Viability of the Local Economy via Tourism • Development and Maintenance of Infrastructure • Development of Reliable and Sustainable Transportation • Need to Grow the Year-Round Population |

An island in jeopardy

After being pummeled by Hurricane Sandy in 2012 and facing eroding land and a dwindling population, almost anyone else would have gobbled up a $2 million offer from the state to buy and demolish homes.

But not Smith Islanders.

“That was our wake-up call,” recalls Somers. “I’d say 99.5 percent of the island was against the buyouts. There are some people on the island that tend to want to leave things the same, but after the thought of losing our home, everyone banded together and accepted that we need to change.”

Duck hunting; by Stephen Badger

Residents took a leap of faith and looked beyond their close-knit community for help. They collaborated with federal and state agencies, county officials and planning firms to outline a blueprint of ideas and strategies.

Chris Cortina, a Department of Natural Resources planner, has been involved in these efforts and notes, “It is the community that will drive a path forward based on their culture, heritage, values and priorities.”

Infrastructure

Back in Ewell, Roland “Pal” Bradshaw stands waiting for us at the docks with his minivan. With little-to-no cell service, I’m surprised to see our ride is right on time, ready to show us more of the island.

Bradshaw has lived on the island his whole life and doesn’t feel like much has changed. “There’s less people now though,” he says.

As we drive past an abandoned home with a huge fallen tree, Bradshaw stops the van. He and Somers explain this is an example of the “develop and maintain infrastructure” theme.

The toppled tree juts into the road. A property dispute has stalled any action to remove it. “This should be an enforceable issue,” Bradshaw says emphatically.

To begin such needed improvements, Smith Island is submitting a proposal along with the Maryland Department of Planning and Somerset County to conduct a study on an enhanced stormwater management system. Smith Island United, a community group turned nonprofit, is also seeking funds for repairs and upgrades to its docks.

A Smith Island Cruises boat; by Stephen Badger

Reliable transportation

Our next stop is Betty Jo Tyler’s home to learn about her family’s business—Smith Island Cruises. We knock on the door and wait. Tyler runs up behind us, apologizing for being a little late.

“I got held up at the Bayside,” she explains as she crosses the lawn. The Bayside Inn, another family business, is one of the few places to grab a bite.

Tyler is younger than I expected and full of energy. She leads us into her home, a warm haven on a chilly day. Pictures of her family line the walls, and I get the sense this is a happy home.

Her father started the company, which operates daily from Memorial Day through mid-October offering 40-minute cruises aboard the Twister or the Chelsea Lane Tyler. Betty Jo’s brother expanded the business to also operate as the floating school bus.

In addition to the Tyler fleet, three passenger ferries operate between Crisfield and Smith Island. The Captain Jason II runs to both Tylerton and Ewell, while the Captain Jason and the Island Belle provide service to Ewell. The schedule is more limited during fall, winter and early spring, and evening services vary depending on demand.

Most islanders would like to see transportation improved to include a more stable evening schedule so residents can make runs to the mainland for essential needs. A more frequent and reliable ferry schedule also would entice additional tourists.

Smith Island United is in conversations with the Maryland Transit Authority about a ferry transportation feasibility study that would address ways to enhance the current system. “We are hoping to secure some grants or a transportation subsidy to help with another daily run,” says Somers as we leave the Tyler residence and walk back to the marina, gravel crunching under our feet.

Islanders wave at Somers as we walk by. He greets every person by name and asks about their family.

Tourism

One name I keep hearing is Gretchen Maneval. Despite the fact that she is a “newcomer” to the island, residents hold her in high regard. She serves an important role: the implementation coordinator for the vision plan.

“I first went to the island for a field trip in high school,” Maneval explains over the phone when I ask about her connection to the island. “Twenty years later, my family and I rented a house. It was transformative, a transcendent experience.

“We reveled in the warm and welcoming community, and loved being immersed in nature. My husband and I looked at each other and felt like we had always been here. We made the decision to scrape together our savings for the down payment on a house in Tylerton.”

Maneval calls it the best decision they’ve ever made. The couple lives in Baltimore with their two young sons, but spends a lot of their time on the island. They wanted their boys to experience a place where everyone knows and supports each other, and where they can soak up the incredible work ethic of the islanders.

Martin National Wildlife Refuge; by Stephen Badger

“It is so important to us that our boys know about life beyond the city,” Maneval says. “I want them to learn about the environment and science firsthand. I want them to know that there are jobs where you can work off of the bounty of our natural resources and, at the same time, work to preserve them.”

Maneval, a neighborhood planner by trade, came at the perfect time to help with the launch and implementation of the vision plan.

“It is such an honor to participate in this renaissance,” she says.

Maneval and Smith Island United have already obtained funds for increased tourism signage as well as other vision plan goals.

Watermen’s culture

Our final stop of the day is the village of Tylerton, year-round population, 44.

On the boat ride over, Somers points out the Martin National Wildlife Refuge that was established in 1954 when the late Glenn L. Martin donated 2,500 acres to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The refuge’s new project, an $8.5 million living shoreline, stands as a beacon of hope to islanders—a tangible sign that the government has not given up on them.

“Our grandparents were so against this refuge,” Somers says. “They didn’t want the federal government coming in and taking over parts of our land. They would roll over in their graves if they knew this refuge is saving the island today.”

Approaching Mary Ada’s house; by Stephen Badger

The project is expected to slow shoreline erosion, providing benefits to fish and wildlife as well as humans. It should protect and restore saltwater habitats important to the soft crab fishery too—music to local watermen’s ears. This project also sets a precedent for potential funding and plans for a similar project for the village of Rhodes Point, a project Smith Islanders have been advocating for years.

With watermen top of mind, we visit the home of Mary Ada Marshall, Smith Island Cake maker extraordinaire, and her waterman husband, Dwight. Their home, a well-kept Cape Cod with a white picket fence, is a few steps from the Tylerton marina.

Mary Ada greets us, and to my delight, offers to whip up a cake. This is the woman who lobbied to make the cake the official Maryland state dessert. I am in the presence of greatness. (Click here for the recipe!)

Smith Island cake; by Stephen Badger

I sit in on the couch in the living room and notice religious psalms stenciled around the home. The artwork reminds me of something Somers said at the beginning of the tour: the Methodist church is an important part of the culture here.

As the sweet smells of chocolate waft in from the kitchen, Dwight sits in a recliner across from me and discusses life as a waterman and the Smith Island plan.

“At first, while we thought [the vision plan] was a good idea, we were worried it would fizzle out,” he says. “But the ideas have held on and the plan has grown. Knowledgeable folks like Gretchen and scientists have helped us get through the red tape and actually do something.”

A life-long waterman, Dwight feels the industry is overregulated with constantly changing rules, making it hard to keep up. “You can make money, but you have to work hard,” he says. “A lot of our youth get an education on the mainland now rather than getting into the industry. We need to help grow young watermen.”

To that point, Maneval says, “There is good news on this front. We recently received funding for a new apprenticeship program to recruit aspiring watermen and preserve the livelihood and heritage. The program will pair veteran watermen with those hoping to get into the industry. It will also provide scholarships for people seeking captain’s licenses and help with upfront capital investments such as boats and equipment.”

She goes on to explain, “We need to bolster and support our watermen. We want to see this important legacy continue into the next generation. Preserving the watermen’s livelihood and culture is one of our top priorities.”

| Funding the renaissance Smith Island recently submitted an application to be designated a Sustainable Community so it can qualify for economic development funding from the state.

In other good news, Ewell Elementary students can now share their culture with the world while learning about faraway places, thanks to a new distance learning technology grant. Plans for partnering island and mainland communities around the world are in the works, as are virtual field trips and other projects to enhance the school’s curriculum. |

Hope for the community

As we make our way back to the mainland, Somers asks me what I think about Smith Island now.

I tell him I already know this has been a day I will remember for a long time; this tiny island makes a big first impression.

You can’t help but notice the pride the islanders feel about their home and, after visiting, it is easy to see why. What an amazing place: a true community bound by a rich history, faith, the Chesapeake Bay and hard work.

Somers nods in agreement.

He says the goal of the plan—the driving force of the community—is to sustain what they have for future generations.

“We want to balance our culture with the mainland,” he adds. “I look at every person who visits as someone who might fall in love with it and help us achieve our goals.”

“Who knows,” he says with a cheeky grin, “maybe it will be you.”

Article by Kristen Peterson—Department of Natural Resources senior communications manager.

Appears in Vol. 19, No. 2 of the Maryland Natural Resource magazine, spring 2016.

1-888-373-7888

1-888-373-7888 233733

233733