Piscataway-Conoy: Rejuvenating ancestral ties to southern parks

When English explorer John Smith arrived in what is now Maryland in 1608, he was astounded by the bounty that would later become the lifeblood of its colonization. He noted that there was, “No place more perfect for man’s habitation,” than the Chesapeake Bay. And he was right. The bay and its rivers offered a hearty supply of crabs, fish, oysters and waterfowl, while the forests and hills teemed with bear, deer, fox, rabbit, turkey and game birds of all kind. Maryland was a virtual paradise with seemingly endless resources. The English had discovered what native people had known for millennia.

The first known inhabitants of Maryland were Paleo-Indians who had gradually migrated here from other parts of the continent following bison, caribou and mammoth, and began to establish permanent settlements along its rivers and streams. By the first millennium B.C.E., Maryland was home to about 40 tribes, most of which were in the Algonquin language family. They traded with other tribes as far away as New York and Ohio, and established a complex society.

Territory and structure

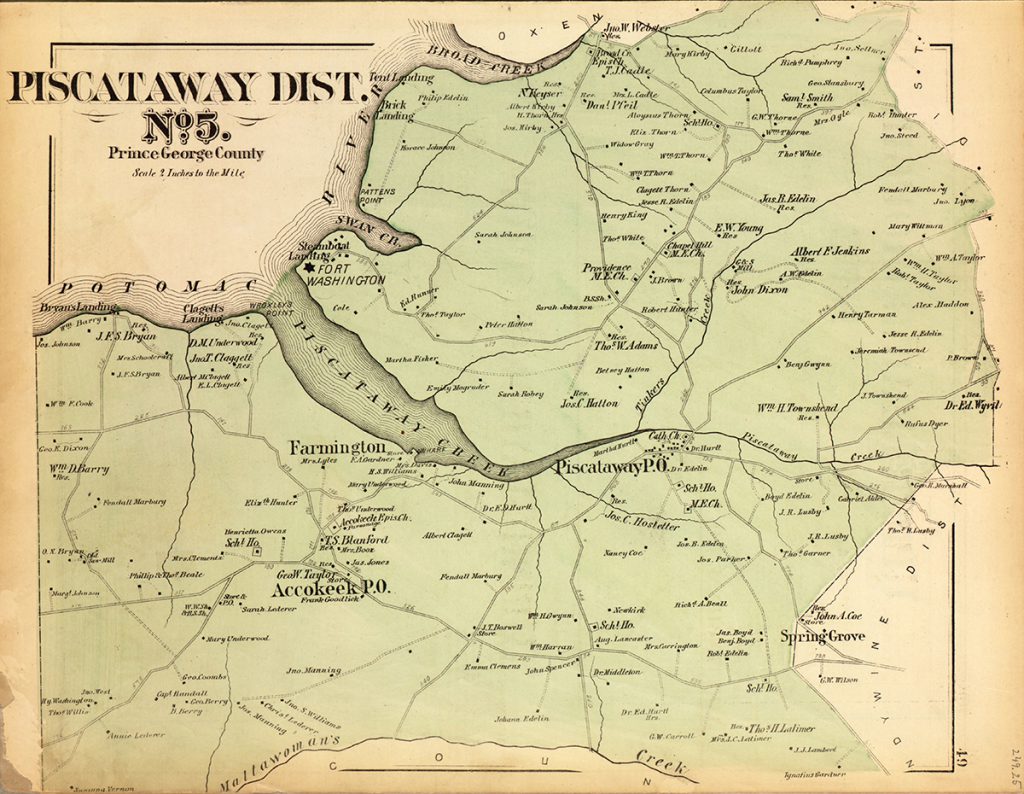

By the time the Europeans embarked on the New World at the dawn of the 17th century, the Piscataway was the largest and most powerful tribal nation in the lands between the Chesapeake Bay and Potomac River. Traditional territory primarily included present-day Charles, Prince George’s and St. Mary’s counties, extended north into Baltimore County and west to the foothills of the Appalachians.

As with other tribes, smaller Piscataway bands—including the Chaptico, Moyaone, Nanjemoy and Potapoco—allied themselves under the rule of a werowance for the purposes of defense and trade. The werowance appointed leaders to the various villages and settlements within the tribe. At the peak of their power in the 16th century, the title of werowance was replaced by a tayac, which was the equivalent to an ancestral king.

Lost community

Colonization was tumultuous for the Piscataway. Already facing aggressive incursions by the Susquehannocks from the north, they began to slowly lose control of their ancestral lands to settlers. Colonial governments granted the Piscataway reservations called manors, but by 1800, even those rights were retracted.

Their alliance began to crumble as the various bands splintered and sought new lands. The largest contingent of the tribe, by this time known as the Conoy, migrated to Pennsylvania and settled for a time by the Susquehanna River with their former enemies—the Haudenosaunee—and sought the protection of German Christians.

The American Revolution took a toll on a number of tribes as they allied with one side or the other. By the end of the war, their villages were devastated. The Piscataway-Conoy were not spared this tragedy, and their remaining numbers were scattered. Some traveled northwest to what is now Detroit and parts of Canada, where they were absorbed into local tribes. Today, their descendants live with the Six Nations of the Grand River First Nation in Ontario. Others fled south where they merged with various tribes in North Carolina. By the beginning of the 18th century, the Piscataway had disappeared.

Through it all, a small number of the tribe remained in Southern Maryland, scattered among the towns and villages, no longer a unified people. Over the years, they gradually melted into the local fabric, living quiet, rural lives.

The Piscataway lost something more than their tribe; they lost their identity as a people. The government at the time did not have a census category for Native Americans, so they were counted as and considered “mulatto” or “negro.” Not only did society not view them as Piscataway, they were not even seen as Native Americans. Although they still self-identified as Piscataway, their traditions faded with time. They were regarded as outsiders in their own communities, neither white nor black, but something different and undefined.

Reclaiming identity

In the 1970s, on the heels of the Civil Rights Era, the Pan-Indian movement inspired Native American groups all over the nation to reclaim their rights and identities, and to fight for recognition in a society that had marginalized them for hundreds of years.

Some Piscataway descendants, who were often belittled and discriminated against within their own communities in Southern Maryland, saw an opportunity to recover their traditional way of life. Several individuals and groups, initially working independently of each other, started the long process of tribal recognition by the state.

Because so much of their history was lost over time, people like Mervin Savoy of the Piscataway-Conoy Federation and Sub-Tribes and Billy Tayac of the Piscataway Indian Nation spent years reassembling the culture from written records and oral tradition. Although the government did not keep records on the Piscataway people, the Catholic Church—to which they were adherents—held a treasure trove of family records and other information, which helped identify more than 5,000 Marylanders as hereditary members of the tribe.

For decades, the Piscataway worked with the state—specifically the Maryland Commission on Indian Affairs—for official recognition of their tribe. At stake was not just cultural acknowledgement and acceptance, but access to federal funds for education, housing, public health and other programs. Finally, in January 2012 at a ceremony in Annapolis, representatives and leaders were finally officially recognized by executive order confirming what they have always known: that they are a distinct people with a long cultural history in Maryland that goes back centuries.

Modern connections

Since gaining recognition, the Piscataway have flourished, celebrating their culture with traditional events such as the Seed Gathering in early spring, the Feast from the Waters in early summer and a Green Corn Festival in late summer. This November, the tribe will partner with the Maryland Park Service during the Greeting of the Geese event at Merkle Wildlife Sanctuary.

In fact, the Piscataway have a close relationship with the Maryland Park Service in the form of a long-term agreement that allows the use of Merkle and Chapel Point State Park, both of which have deep cultural significance to the tribe. The Piscataway use the park facilities for ceremonies, cultural education and interpretive programs, and as a venue to forge cultural connections with other Marylanders by offering classes and guided kayak trips along the waters that have sustained their people for centuries.

Today, the Piscataway number in the thousands, with more being identified via genealogical records. The restoration of their culture and history is a tremendous point of pride for tribal members who, for so long, were marginalized and forgotten in their own ancestral home.

What’s more, that pride is shared by the people of Maryland, as their past is a part of our shared culture and history.

Article by Tim Hamilton—Maryland Park Service business and marketing manager. Appears in Vol. 21, No. 4 of the Maryland Natural Resource magazine, fall 2018.

1-888-373-7888

1-888-373-7888 233733

233733