Maryland Rocks: Amateur mineral hunters find treasure

Rockhounding: it’s a passion shared by amateur geologists who hunt for and collect rocks and minerals out in the wild for their study and enjoyment.

It’s a hobby anyone can begin simply by exploring within their own backyard, then expanding to the neighborhood and beyond.

To get started, you’ll need some tools: a rock hammer and magnifying glass, a notebook, eye protection, geology references, sample bags and a backpack if you plan to collect.

Lay of the land

The most important thing to have on hand is information on where you can or can’t conduct your search safely and legally.

You may collect on privately owned lands, provided you have consent from the owner. Collecting is prohibited—and generally unsafe—along major roadways. Less busy roads are all right, but always watch for vehicles and wear brightly colored clothing.

Public lands are completely off-limits to help protect our shared natural resources. Therefore, removal of rocks and minerals is prohibited in all Maryland state parks, natural resources management areas, state battlefields, rail trails and other state-managed lands.

Federal and local governments may also have restrictions, so always check the rules before you search.

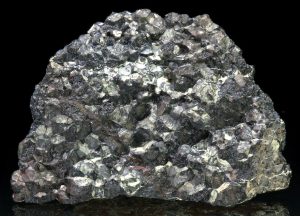

Chromite; courtesy of Chromite Weinrich Minerals, Inc All that glitters… might be chromite ore After the Civil War, gold was mined for a time, but unlike the gold fields on the West Coast, Maryland’s gold rush never amounted to much. By the early 1900s, the practice ceased—there just wasn’t enough of the mineral to be profitable. Many sites where gold was found have been developed or are privately owned and inaccessible. |

What’s out there?

Due to its diversity of terrain, Maryland has been called America in Miniature—and that’s true both above and below the ground. For such a small state, Maryland has an incredibly rich and diverse geological heritage, with all three classes of rocks represented: igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic.

All rocks and sediments are made of minerals, and more than one hundred individual rock and sediment units are recognized in Maryland. The type of rock and sediment mainly determines what types of minerals can be found within, but other factors such as mineral-rich groundwater, cracks, fractures and voids in the rock, and the chemistry of the overlying rock units can influence mineral formation.

Quartz, mica and feldspars are the most common. Less common minerals include calcite, garnet, tourmaline, siderite, pyrite, hematite, limonite and hornblende. The minerals may be small—almost microscopic—and may not appear as textbook examples of crystals, but they are out there.

There are no precious or semi-precious “gem quality” crystals or minerals in Maryland.

Every so often, someone may come up with a more unusual find, such as beryl, in some of the igneous pegmatite rocks in the Piedmont, but such instances are rare. Not too long ago, a crystal of amethyst was reportedly recovered from the Silver Spring area and stored in the Smithsonian.

Diverse geology

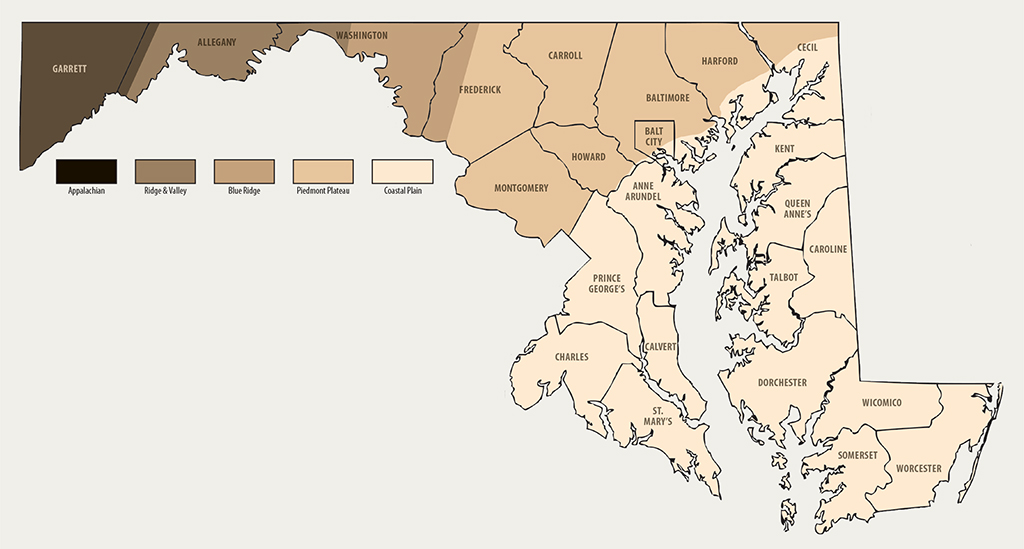

Maryland is divided into five physiographic provinces, each with their own distinguishing types of geology.

The Coastal Plain Province

This is the youngest province and consists of a nearly horizontal, southeastwardly sloping wedge of sediments over 8,000 feet thick. They are primarily clays, gravels, marls, sands and silts ranging in age from 100 million years near Baltimore to new sediments forming today along Assateague Island and the Atlantic Ocean.

The Piedmont Plateau Province

This region contains some of the state’s oldest rocks, dating between 500 million and 1.1 billion years old. The rocks are igneous, metamorphosed igneous and metamorphosed sedimentary, and have been extremely warped and deformed as a result of numerous continental collisions. The Piedmont is home to one of Maryland’s two oldest rocks, the 1.1-billion-year-old Baltimore Gneiss.

The Blue Ridge Province

The smallest province is defined by Catoctin Mountain to the east and South Mountain to the west. These mountains are limbs of an inverted U-shaped geologic structure called an anticline, which after hundreds of millions of years has eroded in the center exposing the other 1.1 billion-year-old rock, the Middletown Granite-Gneiss. The younger rocks overlying the granite-gneiss are of volcanic and sedimentary origin.

The Ridge and Valley

West of the Blue Ridge, this province is comprised of sedimentary rocks, conglomerates, sandstones, silt-stones, shales and limestones ranging from 544

million to 300 million years old. These rock formations were once flat lying sediments similar to Coastal Plain, but were tightly folded into anticlines, and their opposite geologic structure, synclines.

The Appalachian Plateaus

This province contains many of the same sedimentary rocks found in the western part of the Ridge and Valley, as well as the same geologic structure, anticlines and synclines; but these structures have not been as tightly folded.

From the shores westward to the mountains, the state’s elevation progressively rises: from sea level at the ocean to 1,100 feet in Carroll County to 1,500 feet in Frederick County to 2,500 feet in Allegany County. Some of the state’s highest mountains are in the Appalachian Plateaus, including the highest point, Garrett County’s Hoye Crest, at 3,360 feet.

A modest reward

When you travel away from the populated areas, there are more chances to find open grounds where rock outcrops are exposed. Western Maryland beyond Frederick yields the most, although it consists of sedimentary rocks, which do not form many standout minerals.

Unfortunately, most of Maryland’s amazing geology is hidden from us. Unlike southwestern states, the entire eastern region is heavily vegetated. What’s revealed to us in outcrops is exposed to the elements that wear away any surface minerals. Therefore, finding that eye-catching, jaw-dropping gemstone isn’t likely on any given search, and success requires being in the right place at the right time. Until a mineral reveals itself from the depths of the earth, you don’t know what’s beneath you.

Most finds don’t have monetary value. The real value of your find is that you found it; you saw something special in that chunk of rock to pick it up and put it in your pack. That value increases when you learn about them: how they formed, their age, their mineral content and so much more.

Article by Richard Ortt—Maryland Geological Survey director. Appears in Vol. 21, No. 3 of the Maryland Natural Resource magazine, summer 2018.

1-888-373-7888

1-888-373-7888 233733

233733