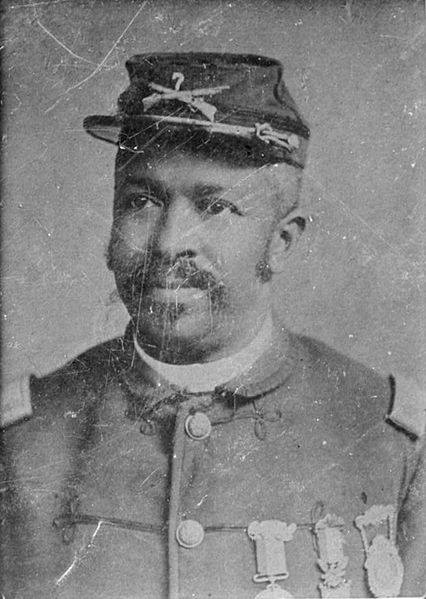

Christian Fleetwood, The Maryland 4th U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment

INTRODUCTION

February has been set aside to reflect and honor the men and women of color who have been integral to the building, strengthening, defending, and advancing of the United States. Maryland’s military history is replete with the achievements of African American Soldiers, whose stories are more remarkable given the discrimination under which they lived and worked. Below is the story of Baltimorean Christian Fleetwood and Maryland’s 4th United States Colored Infantry (USCI, also referred to as US Colored Troops, USCT), told through the lens of the U.S. Army values. While their actions in one battle led to 14 Soldiers receiving the Medal of Honor, the men of the 4th USCI lived the U.S. Army values throughout their enlistment, despite discrimination and monumental obstacles.

RESPECT

The year was 1863, and the Civil War was in full swing. As a border state, Maryland consisted of free and enslaved people, abolitionists, and slaveholders. Because of its geographic location, U.S. Army Maj. Gen. Robert Schenck was concerned that Lee would attack Baltimore. He directed that male civilian Baltimoreans, mostly African Americans, be pressed into service to build fortifications around Baltimore. The attack did not materialize, but Schenck was impressed by the African Americans’ willingness to continue to serve, even after their forced labor. In early July 1863, he requested and received approval to raise a segregated Maryland unit composed of freeborn and formerly enslaved people of African descent. The 4th United States Colored Infantry (USCI) would be constituted in Maryland, with U.S. Army Col. William Birney leading the recruitment effort.

LOYALTY

Raising a regiment of African Americans in Maryland proved more difficult than expected. The first hurdle to overcome was the pay differential. Black Soldiers would be paid $10 per month, rather than the $13 per month that White Soldiers were paid. Additionally, Black Soldiers were docked $3 per month for their uniform, which was of lower grade than White Soldiers, who did not pay for his uniform.

The bounty (bonus) received by White enlistees in Maryland averaged $100 – but the African American Soldiers were initially barred from receiving any bounty. Lastly, all units consisting of African Americans were led by White officers so the highest rank a Black Soldier could achieve was Sergeant Major. Despite the obvious discrimination, the regiment filled out to over 1,000 men who hoped that their loyalty to the Union would result in tangible advancements as well as freedom for all enslaved people in the United States.

DUTY

Although expressing an interest in volunteering, Fleetwood hesitated. In fact, he met with U.S. Army Col. William Birney early in July, who offered him the rank of sergeant major should he enlist. Fleetwood, however, did not commit until August 17, 1863. Within a few days of enlistment, he was designated the regimental sergeant major. Soon thereafter, the 4th USCI joined the all-Black, 3rd Division, XVIII Army Corps under Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler’s Army of the James. Butler understood the value of enlisting African Americans and recognized that the Black Soldier would fight better if treated more equally.

On December 5, 1863, he issued General Order 46, directing, among other items, all Black Soldiers under his command to be outfitted in the same uniform, shoes, weapons, and equipment like the White Soldiers. The order also directed that the Black NCOs receive the same bonus as White NCOs. Although he could not solve the overall pay gap, Butler did write to Congress requesting that the $3 deficit be rectified, noting that “the colored man fills an equal space in ranks while he lives, and an equal grave when he falls.” Unfortunately, it was not until September 1864, after many Black Soldiers had already given their lives when Congress acted.

SELFLESS SERVICE

The U.S. Army of the James Encampment at Ft. Yorktown, Virginia for the winter. In between his military duties, Fleetwood assisted the regimental chaplain to begin religious services and establish a permanent chapel. They and other educated Soldiers from the regiment organized and conducted day and night, academic classes, for their illiterate comrades, as well as educating the local freed African American men, women, and children. At one point, over 300 African Americans were enrolled in these classes.

HONOR

While at Camp Yorktown, the 4th USCI joined other regiments in conducting a series of raids around the countryside. They also completed a stint in guarding Confederate prisoners at Point Lookout, Maryland. Their first official encounter with enemy fire occurred during Butler’s failed Bermuda Hundred Campaign on May 18, 1864. They were assigned to guard the U.S. Army’s left flank on the bank of the James River. Although not involved with the main battle, they did engage briefly with a Confederate unit that resulted in two USCT casualties. Their discipline during that engagement was noted in the daily report.

The 4th USCI again saw action on June 14-15 during the Petersburg Campaign. In their first charge, the 4th overran their position, exposing themselves to brutal gunfire with more than 120 men killed or wounded. After regrouping, their second attempt ended in successfully capturing a vital sector of the Confederate position. Unfortunately, the overall attack failed to capture Petersburg. Grant resorted to the siege tactic late in June.

PERSONAL COURAGE

In the middle of September, Grant launched a diversionary attack on the Confederate defenses around Richmond. On September 29th, the U.S. Army of the James positioned below Confederate fortifications at the base of New Market Heights.  The 4th USCI would be a critical element in the attack. In fact, they would be the first to make contact and would have to sustain the attack until the 6th USCI reinforced them. At 5:30 a.m. the bugle sounded, and the men followed the colors, quickly miring in the swamp that lay between them and the enemy. Those that made it through had to tear at the log barriers to continue the forward movement.

The 4th USCI would be a critical element in the attack. In fact, they would be the first to make contact and would have to sustain the attack until the 6th USCI reinforced them. At 5:30 a.m. the bugle sounded, and the men followed the colors, quickly miring in the swamp that lay between them and the enemy. Those that made it through had to tear at the log barriers to continue the forward movement.

During the attack, the regimental color bearer was shot and the flag fell. The U.S. flag bearer picked up the colors and continued forward, with a flag in either hand. However, he, too, was wounded and the Soldiers’ momentum faltered. Unable to rise, he cried, “Boys, save the colors!” Fleetwood grabbed the U.S. flag while Cpl. Charles Veal, Company D, took the regimental standards. Planting the flags before the breastworks, the two men called for their comrades to breach the fortifications. Miraculously, neither man was hit although the flags were torn almost to streamers.

Despite the courage shown by the men, the assault was doomed, and the officers recalled the men of the 4th, while the 6th USCI who had followed the 4th, then bore the brunt of Confederate fire. By the end of the second day, the Union had captured the targeted forts, thanks in large part to the courage and tenacity of the 4th USCI, led by Sgt. Maj. Fleetwood and Cpl. Veal.

INTEGRITY

In all, the 4th USCI would participate in six major engagements associated with the Petersburg Campaign. Maj. Gen. Butler recognized the gallantry and courage of his men and ensured that 14 African Americans in his command were awarded Medals of Honor for their actions.